“Human salvation lies in the hands of the creatively maladjusted.”—Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

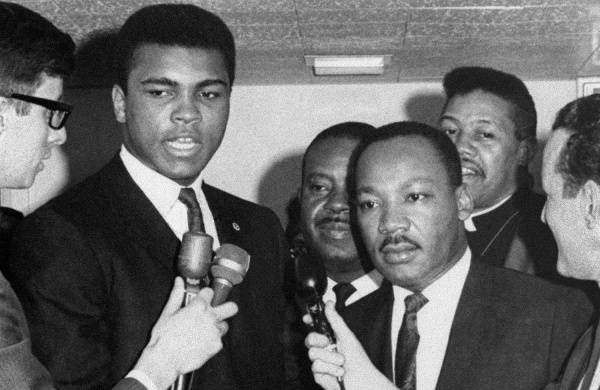

They were both proud sons of the South. They were both African-American. Their birthdays were days apart. They shared common cause and shocked the world, but in different ways and on different platforms.

Despite their similarities, Muhammad Ali and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. were on opposite ends of the political spectrum. King’s foundation was the church. He believed in integration. He was a paradigm of nonviolence who was inspired by Mahatma Gandhi.

Ali, by contrast, as soon as he won the heavyweight title from Sonny Liston in 1964, changed his name from Cassius Clay to Muhammad Ali (“Cassius Clay is a slave name. I didn’t choose it and I don’t want it”) and declared his allegiance to the Nation of Islam. His inspiration was the segregationist firebrand, Malcolm X.

King and Malcolm X, despite similar objectives, were fighting against what the other represented, at least initially.

“He got the peace prize, we got the problem,” said Malcolm X about Dr. King. “If I’m following a general, and he’s leading me into a battle, and the enemy tends to give him rewards, or awards, I get suspicious of him. Especially if he gets a peace award before the war is over.”

King was no more enamored of Malcolm X and what he espoused.

“I met Malcolm X once in Washington,” said King during an interview in Playboy magazine, “but circumstances didn’t enable me to talk with him for more than a minute. He is very articulate … but I totally disagree with many of his political and philosophical views—at least insofar as I understand where he now stands. I don’t want to seem to sound self-righteous, or absolutist, or that I think I have the only truth, the only way. Maybe he does have some of the answer. I don’t know how he feels now, but I know that I have often wished that he would talk less of violence, because violence is not going to solve our problem. And in his litany of articulating the despair of the Negro without offering any positive, creative alternative, I feel that Malcolm has done himself and our people a great disservice. Fiery, demagogic oratory in the black ghettos, urging Negroes to arm themselves and prepare to engage in violence, as he has done, can reap nothing but grief.”

Grief was eventually was visited upon both men, in the form of assassins’ bullets, but as Malcolm X said, and to which Dr. King agreed, “It is a time for martyrs now, and if I am to be one, it will be for the cause of brotherhood.”

Just as Malcolm X and Dr. King evolved, Muhammad Ali evolved as well.

“If there was an Olympic sport for number of death threats received back then,” said John Carlos, the radical 1968 Olympian, “King and Ali would be fighting for the gold.”

Ali and Dr. King came together in 1967 when King voiced his objection to the war in Vietnam. Freedom marches and integrating lunch counters was bad enough, but by taking on the military-industrial complex, with its endless wars and rapacious war profiteers, many felt that King had gone too far.

But Ali felt otherwise. He had already been stripped of his title by refusing to fight in Vietnam (“I ain’t got no quarrel with the Vietcong,” he famously said. “No Vietcong ever called me nigger”) and was facing the threat of five-year in prison for having taken another principled stand.

“Like Muhammad Ali puts it,” said King, “we are all—black and brown and poor—victims of the same system of oppression.”

At a fair-housing rally in Louisville, Kentucky, Ali and King finally stood side by side.

“In your struggle for freedom, justice and equality, I am with you,” Ali said to Dr. King. “I came to Louisville because I could not remain silent while my own people, many I grew up with, many I went to school with, many my blood relatives, were being beaten, stomped and kicked in the streets simply because they want freedom, and justice and equality in housing.”

Freedom, justice and equality continue to remain elusive, but what Ali said many years ago is no less true today.

“He who is not courageous enough to take risks will accomplish nothing in life.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GDYGHmfiFQg

This article was penned by the author who is not related to the WBA and the statements, expressions or opinions referenced herein are that of the author alone and not the WBA.