Seventy-one years ago—on Wednesday, the 26th of last month—Argentine boxing carved its name into history when Pascual Pérez, famously known as El Pequeño Gigante (The Little Giant), captured the flyweight world championship under the banner of what would later become the World Boxing Association (WBA). In doing so, he became Argentina’s first-ever world champion, securing his place among the nation’s most iconic sporting figures across its three most popular disciplines: soccer, auto racing, and boxing.

Pérez’s breakthrough came at Tokyo’s famed Korakuen Hall, where he floored Japan’s Yoshio Shirai in the second and twelfth rounds en route to a clear, unanimous decision victory. The scorecards told the story: referee Jack Sullivan had it 146–143, while judges Bill Pacheco and Kuniharu Hayashi turned in tallies of 143–139 and 145–143, respectively.

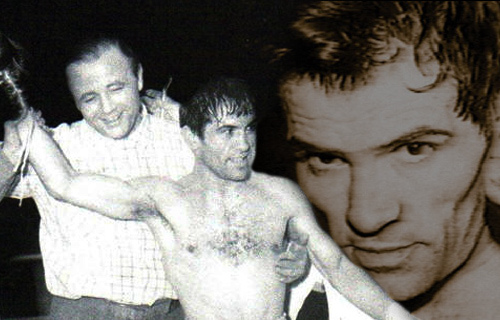

Born in Tupungato, Mendoza, on May 4, 1926—the youngest of nine children in a family of vineyard workers—Pérez’s triumph ignited national celebrations back home. Days after his victory, he arrived at Buenos Aires’ Ezeiza Airport to a hero’s welcome, complete with banners, chants, and an ecstatic crowd led by then-president Juan Domingo Perón himself.

In the decades that followed, Pérez’s crowning moment inspired a lineage of champions: 39 Argentine men and 25 women would go on to claim world titles. In Latin America, only Mexico—with well over 100 male world champions—surpasses Argentina in total world crown holders.

Yet despite his accolades, Pérez never quite reached the level of popular idolatry enjoyed by countrymen such as José María “Mono” Gatica, Nicolino “El Intocable” Locche, or the legendary middleweight monarch Carlos Monzón (reigning from 1970 to 1977). Part of the reason, experts say, was charisma—or a perceived lack thereof—even though Pérez had already cemented greatness years earlier as the 1948 Olympic flyweight gold medalist in London, where he won five bouts, three by RSC, and edged Italy’s Spartacus Bandinelli in a grueling final.

Disappointed after being unjustly removed from Argentina’s squad for the 1952 Helsinki Olympics, Pérez turned professional four years later under the guidance of Lázaro Koci, the celebrated architect of modern Argentine boxing. Standing only 5 feet (1.52 m), almost always the smaller fighter, Pérez nonetheless “hit like a mule,” as one of his biographers put it. He blasted through his first 18 opponents by knockout before Juan Bishop became the first to last the distance in bout No. 19. In 1953, he captured the vacant Argentine flyweight title with a KO of Marcelo Quiroga.

⸻

First Encounter with Shirai

Pérez’s initial meeting with Yoshio Shirai came thanks to the efforts of Argentina’s ambassador to Japan, Carlos Quiroz—at the direct request of President Perón. Their clash was staged on July 24, 1954, during the grand opening of Luna Park, the cathedral of Argentine boxing. The ten-rounder ended in a draw, effectively positioning Pérez for a world title opportunity.

That opportunity arrived on November 26, 1954. This time, Pérez left no doubt, dominating Shirai with authority and claiming the world crown in the performance that defines this story.

⸻

Title Defenses and the Decline

Regarded by historians as one of the three greatest flyweights of all time—alongside Welsh legend Jimmy Wilde and Mexico’s Miguel Canto—Pérez went on to wage an exceptionally active reign: 12 world title bouts and nine successful defenses.

In his first defense, he granted Shirai a rematch at Korakuen Hall on May 30, 1955, knocking him out in five. On January 11, 1956, he defeated the Philippines’ Leo Espinosa over 15 rounds at Luna Park, then stopped Cuba’s Oscar Suárez in eleven that June in Montevideo, Uruguay.

Defense No. 4 came on March 30, 1957, when Pérez blew out England’s Dai Dover in one round at Club Atlético San Lorenzo de Almagro in Buenos Aires. He returned to the same venue that December to halt Spain’s Young Martin in the first round.

Next came Caracas, Venezuela, on April 19, 1958—a national holiday commemorating the country’s Declaration of Independence. Fighting before a packed Nuevo Circo, Pérez survived a six-second knockdown in round two against 22-year-old hometown star Ramón Arias, then took control from the sixth round onward to earn a unanimous decision in a thrilling 15-round war. It was a night of several historic firsts: the first world title fight in Venezuela, the first involving a Venezuelan challenger, and the first sporting event ever broadcast live on Venezuelan television.

Later that year, on December 15, Pérez kept his belt with a unanimous decision over Dommy Ursua at Manila’s Rizal Memorial Coliseum. A globe-trotting champion—his fights in Argentina rarely drew strong crowds—Pérez returned to Japan, outpointing Kenji Yonekura on August 10, 1959, and stopping Sadao Yaoita in their November rematch in Osaka. Yaoita had previously handed Pérez his first professional loss that January in a non-title bout after an eight-year unbeaten run (51-0-1, 37 KOs, one draw).

The reign finally ended on April 16, 1960, when 25-year-old Thai contender Pone Kingpetch, towering at 5’7” (1.70 m), earned a narrow unanimous decision in Bangkok’s Lumpinee Stadium. Kingpetch repeated the feat later that year on September 22, stopping Pérez in eight rounds at the Olympic Auditorium in Los Angeles.

⸻

The Final Years

Even at 34, the old warrior refused to quit. Between 1961 and 1964, he stitched together a 28-fight winning streak—20 by knockout—against mostly modest opposition before dropping three of his final five bouts, culminating in a loss to Panama’s Eugenio Hurtado on March 15, 1964, a month shy of his 38th birthday.

His last seven opponents, with few exceptions such as Colombia’s Bernardo Caraballo, Mexico’s future world champion Efraín “Alacrán” Torres, and the Philippines’ Leo Zuleta, were largely nondescript. Pérez finished with a remarkable ledger: 84 wins (57 KOs), 7 losses (3 by KO), and 1 draw in 92 fights.

In 1997, Pérez was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in Canastota, joining fellow Argentine greats Carlos Monzón, Nicolino Locche, and Víctor Galíndez.

But his final years were marked by hardship. The combination of his 1977 divorce from Herminia Ferch, mother of his two sons, along with financial ruin brought on by deceit from people he trusted, left him nearly destitute. At one point, the former world champion was reduced to shining shoes and begging to survive.

“El León Mendocino,” as fans also called him for his ferocity and technical skill, died in Buenos Aires on January 22, 1977, from hepatic-renal failure at just 50 years and eight months. He is buried at La Chacarita Cemetery in the Argentine capital.