On Saturday, January 17, 2026, it marked 84 years since the birth in Louisville, Kentucky—the most populous city in the state—of the man baptized as Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr., the firstborn son of Odessa Grady Clay and Cassius Marcellus Clay Sr., a sign painter by trade, a womanizer by nature, fond of nightlife, singing, dancing, and the occasional drink.

That boy, the eldest of four siblings in a middle-class family, would later be known throughout his country and the sporting world by his birth name after winning the light heavyweight gold medal at the 1960 Rome Olympic Games. A short time later, after becoming world heavyweight champion at just 22 years of age in February 1964, the world would repeat his name under a new identity: Muhammad Ali, one of the most controversial, charismatic, and influential sports figures of the 20th century and, without question, the most prominent boxer in the annals of the sport.

As a citizen, Ali also distinguished himself through his tireless fight in defense of African Americans in the United States and people around the globe, as well as for followers of Islam, the religion he embraced a couple of years after his stunning victory over Charles “Sonny” Liston, when he won the heavyweight championship for the first time on February 6, 1964, at the Miami Beach Convention Hall. Four months later, on June 25, he defeated Liston again, stopping him in two rounds at the Central Maine Civic Center in Lewiston, Maine.

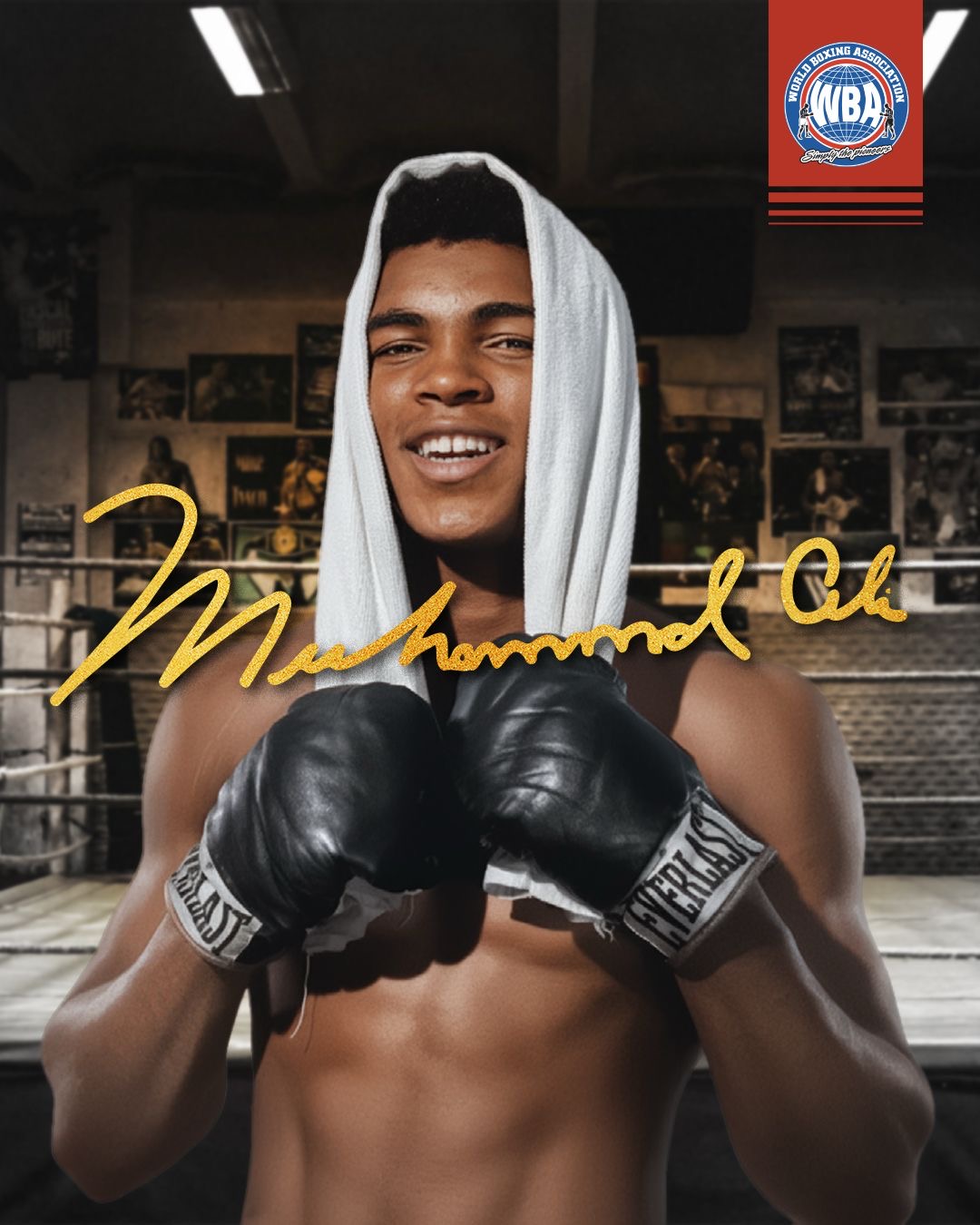

The famous photograph from that bout—one of the most iconic images in world sports—shows the still-named Cassius Clay towering over Liston, urging him to get up. That image illustrates this story.

After defeating Liston for the second time, Clay—now calling himself Muhammad Ali, which translates as “Beloved of God”—went on a dominant run between 1965 and 1967, defeating former world champion Floyd Patterson, Canada’s George Chuvalo, Britain’s Henry Cooper and Brian London, Germany’s Karl Mildenberger, and Americans Cleveland Williams, Ernie Terrell, and Zora Folley, the latter on March 22, 1967.

Following that last bout came his induction notice. On April 26, at a draft office in Houston, the defiant fighter refused to answer the three calls ordering him to don a military uniform. At the time, the U.S. war in Vietnam was at its height. Ali argued—unsuccessfully—that his religion forbade him from going to war and declared himself a conscientious objector. “I ain’t got nothing against the Viet Cong. No Viet Cong ever called me a nigger,” he told the media.

He was sentenced to five years in prison and fined $10,000. In response, the New York State Athletic Commission stripped him of the heavyweight title and revoked his boxing license. Ali was forced to wait three and a half years to return to the ring, which he did only after the U.S. Supreme Court overturned his conviction, sparing him prison time and allowing his comeback. He returned on October 23, 1970, stopping Jerry Quarry in just two rounds.

Ali was blessed with astonishing hand and foot speed for a heavyweight, along with an imposing physical frame at 6-foot-3 (191 cm). Those rare attributes helped him change boxing forever. Never before had a heavyweight moved around the ring with his arms hanging at his sides, dancing with joy and swagger, staring challengingly—and almost mockingly—at his opponent. Fans were enthralled by an athlete who “floated like a butterfly and stung like a bee,” a phrase Ali made famous worldwide, though it was originally coined by his friend and cornerman, the flamboyant Drew “Bundini” Brown, who was every bit as colorful as Ali himself.

When Ali finally walked away from the sport, he had fought 56 bouts, scoring 37 knockouts for a 66.07 percent knockout ratio, with five losses, four of them by decision. He competed in 25 world championship fights, losing three: first to Joe Frazier in March 1971 at Madison Square Garden; then to Leon Spinks in February 1978 at the Las Vegas Hilton; and finally to former sparring partner Larry Holmes, the only man to stop him, in February 1980 at Caesars Palace, when Ali was already a shadow of his former self. Most of those fights were loaded with emotion and massive national and international expectation.

He left behind unforgettable memories that still surface in boxing debates among old-time fans: his epic battles with Sonny Liston, against whom he won the heavyweight crown for the first time and became the first man to rule the division three times in separate reigns; the three wars with Joe “Smokin’” Frazier; the trilogy with former Marine Ken Norton, which Ali won 2–1; the 15-round loss in which he surrendered the WBA belt while fighting with a fractured jaw from the second round; and finally the legendary “Rumble in the Jungle” against George Foreman.

That bout, held on October 30, 1974, in Kinshasa, Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo), is remembered as one of the greatest upsets in boxing history. Ali, widely viewed as a sure victim, stopped Foreman at 2:58 of the eighth round. The fight reportedly drew a global Pay-Per-View audience that surpassed the estimated 530 million viewers who watched the moon landing in 1969.

Ali remains the only three-time lineal heavyweight champion (1964, 1974, 1978) and the only heavyweight to win the WBA title four times (1964, 1974, 1978).

The bout with Foreman, promoted by Don King with the backing of Zairian dictator Mobutu Sese Seko, was the first world title fight staged in Africa. Foreman entered with a terrifying 40–0 record and 37 knockouts, while Ali stood at 44 fights, 34 knockouts, with losses only to Frazier and Norton. The fight took place at 4:00 a.m. local time before a crowd that far exceeded the stadium’s 60,000-seat capacity, chanting relentlessly: “Ali, bumayé!” (“Ali, kill him!”).

Against all predictions—and against trainer Angelo Dundee’s advice to stay at distance—Ali employed his own strategy, rope-a-dope, absorbing Foreman’s punches on his arms and shoulders while taunting him and draining his energy, before unleashing the decisive combination in the eighth round.

Ali’s later years were marked by physical decline and the onset of Parkinson’s disease, diagnosed in September 1984. The once electric master of movement and speech was gradually confined to a wheelchair. His final bouts—against Larry Holmes in 1980 and Trevor Berbick in December 1981—were painful reminders of a legend who stayed too long. The world last saw him in a deeply moving public moment on July 30, 1996, when a visibly trembling Ali lit the Olympic torch at the Atlanta Games.

On June 3, 2016, following complications from respiratory problems that led to septic shock, Muhammad Ali passed away. Married four times and the father of nine children, he is regarded by many as the greatest heavyweight in boxing history, rivaled only by Joe Louis and Jack Johnson. He had been inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in Canastota, New York, 26 years earlier.